"...The spectator will let himself be carried along by the extraordinary images in front of him, by the actors' voices, by the soundtrack, by the music, by the rhythm of the cutting, by the passion of the characters...and to this spectator the film will seem the "easiest" he has ever seen: a film addressed exclusively to his sensibility, to his faculties of sight, hearing, feeling. The story will seem the most realistic, the truest, the one that best corresponds to his daily emotional life..."

These are the words of Nouveau Roman author Alain Robbe-Grillet, who penned the screenplay for Alain Resnais' famously unconventional Nouvelle Vague film Last Year at Marienbad. What he's saying though, that the film is likely to be the gentlest, most malleable viewing experience possible, would undoubtedly contradict with the overwhelming majority of the film's approximately fifty-year audience. The quote also comes from a preface to the screenplay that was published prior to the release of the film, in which Robbe-Grillet sung sweetly about the perfect osmosis between he and Resnais in working on the project, a sentiment that he gradually and bitterly altered in the years after. The discontinuity between his statement and reality however may be by design, posed as yet another unkempt stitch in an already ruffled patchwork, a film that literally (and many would say figuratively) takes game-playing as one of its subjects. For good reason, Resnais and Robbe-Grillet have been named the biggest fibbers and pranksters in the history of the cinema.

I'd like to think though, with its immensely satisfying visual and aural rhymes, its subtle mutations in tone, and the rigorous performances of its two unnamed leads, that Last Year at Marienbad is much more than just a game. Instead, there is some truth in Robbe-Grillet's assertions: the film, through its unusual alchemy of repetition and minor variation, approaches the mechanics of the mind, specifically the way memory and fantasy work within the human brain. Whether or not this results in the kind of viewing Robbe-Grillet predicts is a different question. It is no way an "easy" film, but rather one that constantly asks questions, or perhaps only appears to ask questions. It can be aggravating or hypnotic, off-putting or encouraging, daunting or lean. Why its effect varies so much from viewer to viewer (the film caused one of the most divisive critical responses in film history) is and always will be a massive mystery, but it says a great deal about Resnais and Robbe-Grillet's achievement, and in a way, is naturally symptomatic of a film dealing with the elusive nature of human thought.

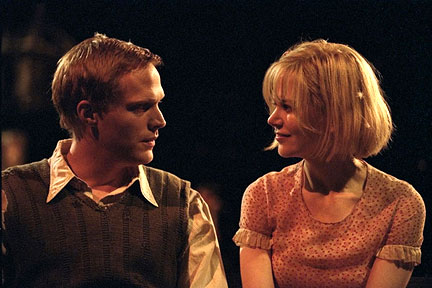

Last Year at Marienbad features three central figures identified only as X, A, and M in the production notes. X (Giorgio Albertazzi), encounters A (Delphine Seyrig) at an opulent hotel getaway somewhere in a void in Europe (possibly Marienbad, but there is no certainty, as the exteriors change conspicuously), and attempts to convince her of their meeting a year back in the same place, where they agreed to reconvene in exactly one year and run away together. Like Resnais' previous fiction debut, Hiroshima, Mon Amour (scripted by Robbe-Grillet's contemporary, Marguerite Duras), the male/female dynamic here takes on an aggressor/resistor stance, with X relentlessly insisting and A guilelessly denying any knowledge of such a meeting. As the film progresses, there are ever-so-slight variations in A's reaction to the stubborn perseverance; most of the time she staidly and somewhat playfully brushes off X, but then her tone grows serious, until in the end the two reach some sort of consensus, though a shaky one at that. X's recollections of specific moments that marked their meeting seem convincing enough to warrant A's continued attention, but he appears to be in pursuit not of a tangible romantic relationship but of something deeper, something essential to his being, something metaphysical perhaps. The enigmatic M, a lanky, stone-faced man who appears to have a significant connection to A, stalks the film in near silence most of the time, strolling down the corridors of the hotel and frequently playing a Chinese strategy game called Nim with X, mirroring the supposed battle between the two over A, and on a larger level emblematic of the film as a whole.

This meeting constitutes the primary conceit of the film, which is more a situation than a plot. Nothing more happens, and it also might be accurate to say that the same thing happens again and again, played out with minor discrepancies. No one scene can be said to have occurred in reality or in the minds of the characters, and with so many fragmented moments to choose from, the film only obscures itself more and more as time passes. We see contradictions arise once again when X's narrated recollections don't match up exactly with the images onscreen, colliding with them in a way that disorients the viewer. Such a mystery yields several potential explanations: X has been lying all along, and his stories are no more certain in his mind than they are in ours; like an instance of déjà vu, X's memories only arise in glimpses, so what he has to work with cognitively is then rearranged as scenes with slight changes; or there is the possibility that the whole film is from the trajectory of A, who is trying with some difficulty to piece together the images created by X's consistent, obstinate words.

An atmosphere of static, free-floating menace permeates through this drama, which Resnais capitalizes on with stunning visualizations of the numerous planes that Last Year at Marienbad inhabits; that is, past, present, future, fantasy, memory, dreams. Sacha Vierny, one of the gifted cinematographers on Hiroshima, lets the camera slide through the hotel and around its premises with both effortless grace and physical detachment, echoing the fluid yet cold forms in the magnificent marble architecture. It is no more likely to focus on its ostensible human subjects than it is to pause and marvel at the icy beauty of its surroundings, tracking across the gilded ceilings, expansive hallways, or palatial spiral staircases as X's voice-over describes the alienating quality of these elements. Yet the human presence in the film tends to be just as lifeless; immobile, unemotional figures dressed in fancy nightwear occupy the spaces in schematic orientations, lending a ghostly peculiarity that certainly, among many other things, influenced Stanley Kubrick in The Shining (1980). Some of the most confounding shots in Marienbad though are the simplest technically, such as the repetitious use of static mirror compositions, which uncomfortably plunge us directly out of the present and into the very embodiment of the temporal refractions that are the film's bread and butter. It is in these moments where Robbe-Grillet's manifesto seems truest, where space and time are obliterated in the name of unique cinematic expression.