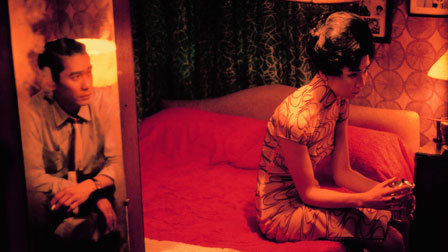

Mr. Chow (Tony Leung) and Mrs. Chan's (Maggie Cheung) coincidental romance is doomed from the start. The two have moved into neighboring apartment rooms in Hong Kong on the same day, and just as soon as this happens they suspect both of their respective traveling spouses of infidelity. In the instance of mutual dejection, they begin seeing each other rather routinely enacting rehearsals of the imagined romantic liaisons of their spouses, a sly narrative device that only superficially masks the pair's own growing attachment. Yet we know from the outset that this is a relationship that will not work, if only for reasons outside their control, and director Wong Kar-Wai laments this fact while emphasizing it through tight domestic compositions and a rich patchwork of fragmentary scenes in which words are schematic and desires are withheld. The acute sense of melancholy and longing that imbues In the Mood for Love is masterfully realized through Wong's impressionistic sensibility, and it results in film that, despite its deliberately elusive narrative, which constitutes a memory of the past rather than a present moment, acquires a plausible emotional register. Everything that is mere stylistic flash in Wong's earlier films works marvelously here, as it's always stressing the underlying emotions and themes in the film, and also - being a film that is consciously constructed of moments as opposed to chronological sequences - the precise feelings inherent in every memory.

The immediate discontinuity between In the Mood for Love and Wong's earlier Hong Kong-set films like Chungking Express and Fallen Angels is the level of design precision. His early films display a burst of Godardian energy, seemingly subject to great spontaneity and fluctuation between script and finished product. Here, no notes are bent. The art direction, costumes, cinematography, and musical cues feel so pre-ordained and exact despite the film's strangely episodic, elliptical nature. Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung's meta performances are assured and mannered yet not without a sense of humor and imperfection, unlike the freewheeling naturalism of Fallen Angels' sprawling, hyper-kinetic bodies in urban spaces. Although the bulk of Wong's core collaborators remain the same (William Chang is the film's editor, and Christopher Doyle once again lends his talent to the film as cinematographer), In the Mood for Love calls upon Wong to adapt. Its story emphasizes ephemerality as well as formality (the setting is of established middle-class adults in a pivotal early 1960's instead of disillusioned twentysomething loners in a more modernized urban environment), so the style works accordingly. Scenes are alarmingly short and to the point but still beautiful, and that is very much the ulterior motive: the lovers' milieu is only deflating and suppressing the impassioned attraction at the core of their encounters.

Yet the pacing of the film also bends to the mechanics of memory on occasion. Because of the fact that Wong ends the film on Mr. Chow during a lush coda in the midst of Cambodian ruins, and positions its final quotes as those of Mr. Chow, In the Mood for Love presumably is the product of his memory. Therefore, moments of glimpsed tenderness between Chow and Chan are normally protracted by Wong through either slow-motion, matched harmoniously with Michael Galasso's mischief-soaked waltz, or nearly imperceptible shutter speed effects which retain real-time diegetic audio (such instances are infinitely more effective than their overuse in Fallen Angels). Mr. Chow savors these fleeting hints at fully expressed love with Mrs. Chan, and through the magic of his mind, and the cinematic medium, he can extend them, fetishize them, and even repeat them, explaining the several repeated scenes (and images) in the film. We are however left without the subjectivity of Mrs. Chan, and her ambivalent, emotionally confused presence in the film leaves her actual thoughts up to interpretation, but through minor, evocative gestures, Wong (and Cheung) suggests that Chan's repressed feelings are reciprocated.

In the Mood for Love is a decidedly personal, introspective work, but it also has a compressed social and political component to it. In a perfect world, free of societal constructs and points of view towards marriage, loyalty, and manners, Mr. Chan and Mrs. Chow would go unrestricted with their desires, falling for each other the moment their first instinctual love bug crawled out. Repressed romances in the face of a collective society is a storytelling plug as old as dirt, identifiable in the literary works of Shakespeare and subsequently throughout film history, most radically practiced by Luis Buñuel. Wong's film breathes interesting new life into this theme because the rapturous, rainy Hong Kong that Mr. Chan and Mrs. Chow occupy is far from being an oppressive area. Rather, the gorgeous wallpaper and meticulously placed old-fashioned cars are reflective of an adequate, even luxurious Hong Kong, and the economic situation of the time is what initially brings the pair together in the adjacent apartments in the city. As the 1960's progressed, the social situations worsened, culminating in a series of subversive riots in 1966 and 1967, when the film spends its final where-they-are-now episodes. The coming-together of Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan occurs at a highly specific time and place, and the precise conditions of their meeting could not be replayed, demonstrating the impact of the public on the personal.

Given the film's adeptness in conveying the intangible through clever visual and editing rhymes, it becomes rather redundant when Wong adds the captions referring to Mr. Chan in the final acts, phrases which add verbal verification to the broader feelings communicated through the film. This has the unfortunate effect of showing and telling, of limiting the potential for cinematic reflection to what is spoken in summation. "The past is something he could see, but not touch. And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct." In the Mood for Love does not need these words because it has an uncanny ability to make us live this experience of transience and forgetting, to truly feel the sensation of a blurred snapshot. Every ecstatic detail - the bottom of a red window shade blowing next to the floor, a cigarette in an ashtray smacked with fresh lipstick, the rotting texture of a cement wall beside the noodle house - accumulates to convey this with expertise. It's a film whose richness confirms Wong Kar-Wai as a major talent.

3 comments:

Carson,

I'm afraid that while I quite enjoyed this film, it didn't come up to the levels of Days of Being Wild, Fallen Angels or Chungking Express.

I didn't get that feeling of repressed emotion or longing or melancholy. I don't know precisely why.

I think there is more 'stylistic flash' in his later films - it's not as energetic but the claustrophobic and precise is flashy in its own way and the design suffocates itself and the story (and not in a good way).

"The art direction, costumes, cinematography, and musical cues feel so pre-ordained and exact despite the film's strangely episodic, elliptical nature."

To me the pre-ordained and exact nature stifled the film, making it feel like a catwalk show. His earlier films had the same melancholy and longing without fetishising it (though I love that close up of Chow taking his hand away from hers, which becomes a wrenching break in slow motion).

Very, very well written but you got out of it something I didn't (unfortunately).

Interesting response, Stephen, because the problems you have with his later work seem to be the exact same problems I have with his early work. Evidently we're working with an elusive director here.

Your contention that his more buttoned-up style a la In the Mood for Love sounds like a broader issue with staunch formalism. I understand that if a director gets too carried away with his or her style (some would say Wes Anderson is an example, though I would disagree), it takes away from the emotional value of the film. I think Wong's work in this film is not too precise as to be nitpicky; he allows for the occasional spontaneity.

This is an interesting criticism on your part, because I know you love Terrence Malick and Michael Mann, and they too have very exacting styles. With the latter, I find myself thinking the same thing you do with In the Mood for Love.

For me, a film like Fallen Angels struggles with a lack of focused pacing. His frenetic camerawork collides jarringly with long sequences like the one in random black and white when the could-be lovers sit inside a cafe as seen through a rainy window. The scene occurs in slow shutter speed, and it goes on for such a long time that I find it irritating in contrast to the rest of the film. If that isn't fetishising, then I don't know what is.

Thanks for the response.

"Your contention that his more buttoned-up style a la In the Mood for Love sounds like a broader issue with staunch formalism."

I don't think I have anything against 'staunch formalism' per se.

"The scene occurs in slow shutter speed, and it goes on for such a long time that I find it irritating in contrast to the rest of the film. If that isn't fetishising, then I don't know what is."

Ah. Well, I agree with you on that scene! It got rather tedious.

Post a Comment