It's easy to miss narrative details of Robert Bresson's Pickpocket. So much becomes of so little. The story, that of a compulsive thief named Michel (Martin LaSalle) and his repetitious existence, is constantly expanding outward and the claustrophobic frames which contain it seem to be choking for breath, looking for a way to accommodate for any plot threads that are left unexplored. Yet this effect is all carefully devised by Bresson to approximate the perspective through which the loner Michel sees the world, and also the one-sided state of mind he has backed himself into. It is with rigidly uncompromising minimalism, eerie silences, and austere performances that Bresson is able to achieve this unique atmosphere. With Pickpocket, he manages to effectively render the damaged subconscious of a criminal by supporting the film throughout with his lead character's narrated diary entries, a technique that acquires the confessional immediacy of Claude Laydu's musings in the aptly named Diary of a Country Priest.

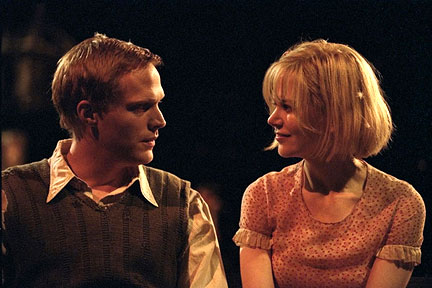

Not only does Pickpocket reach back towards Bresson's own oeuvre, but it also is heavily influenced by one of his favorite writers: Fyodor Dostoyevsky. The film is often said to be the cinematic equivalent of the Russian author's Crime and Punishment, although it makes no attempt to adapt it note-for-note. Both films ponder about the nature of the common man and morality in society and deal with pro(anta?)gonists who commit illegal acts based on a justification of some sort, although the precise one in Michel's case is in question. His character is solemn and blank for the film's entirety despite the several options he has before him that could improve both his spiritual and financial well-being. There is Jeanne (Marika Green), an unassumingly gorgeous woman who lives in the same apartment complex as him and occupies a space directly next to his dying mother. Even when she suspects him of crime, she offers her guidance. There is also Jacques, a teasing friend who nonetheless is willing to help Michel find a job. With all of this help, one assumes he should not feel so alone in the world. Why then, does he resort to pickpocketing?

Bresson's cinema is famously a cinema of questions, questions that permeate through every aspect of the film, be it related to mise-en-scene, narrative, or theme. Where is this scene taking place? Who was he just talking to? What leads him to behave the way he does? These often lead to dead ends when considered logically. But it's also necessary to point out that Bresson wants you to feel before you comprehend, and also wants you to acknowledge that the journey you take to reach supposed answers is just as important if not more important than the answers themselves. It is significant, then, that the title of the film is as succinct and pragmatic as it is; Bresson wants us to first and foremost get inside the head of a pickpocket. Consider the life of a pickpocket: isolated, focused, sneaky, drifting. We experience these traits through Bresson's exquisite cinematography, which creates an endlessly self-contained world of hands, doors, mechanically moving crowds, wallets, and blank glances. Bresson does not show us any exteriors in their entirety, nor does he ever reveal Michel's whole room at once. When on a subway or on the street, the camera stays fixed on Michel, following him as he scouts victims who are diminished to black blurs across the screen. The film's quietly elaborate centerpiece, in which Michel and his new accomplices devise a ballet of theft in the train station, is the towering technical achievement of the film, yet it is never ostentatious. Instead, the form perfectly reflects the action.

The film also makes mindful use of sound as well as image. Reminiscent of Bela Tarr's application of post-synchronized sound, Pickpocket exists in a Paris where the clatter of footsteps is cumulatively louder than the sound of human voices and even motor vehicles. It all works to deindividualize the masses; after all, Michel prefers not to see them as separate people with individual strengths and weaknesses, but rather as a collective whole which he has elevated himself above by reading books. Nearly everyone wears black suits and is ripe for the picking, or pickpocketing, rather. It also should not be noted that hands, which take greatest precedence visually, create not the faintest of sounds. To Bresson, hands tell as much about a person as anything else on a physical body, and here, their silence helps to emphasize their deft movement and underscores the fact that Michel speaks only through action. The whole of his existence is defined by the choices he makes with his hands, as they are both the vehicles of his downfall and the sources of his pleasures.

If pleasure sounds like a impossibility in the life of Michel, take into account the different meanings of the word. When he commits theft, he gets a perverse and - as some critics have argued - sexual thrill out of it, no matter how briefly that thrill lasts. It is the danger of the encounters that excites him, the rush of being inches away from someone breathing on your neck while still slipping a hand into their coat pocket. Pickpocket is indeed a thoughtful inquiry into the way we live our lives, the meaning of our existences, and the shaky divide between right and wrong, but it is also a film that speaks strongly about compulsion and the intangible force that drives people to continue harmful behaviors. Michel gets his due in the end when he foolishly, and perhaps deliberately, steals from an undercover policeman, but his imprisonment is not a judgment on Bresson's part as much as it is another question. When he finally embraces Jeanne between metal bars and the emotion breaks through, reaching a level of transcendence, as Paul Schrader suggests, we wonder whether or not Michel's crimes were worth it.