Lars Von Trier's Dogville is a remarkably dense film unafraid to put forth a discursive string of unsettling questions about the baseness of human nature. This sentence could quite comfortably form the one-line review to any of the Danish director's films, and it's not necessarily always a clear-cut indicator of success. Von Trier's films are hardly prone to elicit black or white opinions, but of what I have seen, Dogville is the one that most closely approaches perfection. The film, three hours long with plenty of intellectual chutzpah, is one whopper of an experience. It is a rock-in-the-shoe of a film, the kind of significant work of art that defies you not to react, to the point where very few next-day reviews will really come across with utmost sincerity. As a disclaimer, it has been three days since I saw Dogville and it has taken me this long to wrestle with my thoughts; the same occurred with his latest provocation Antichrist. Point being, his films have a way of detecting some universal safe zone that exists inside viewers, entering through the back door, and hiding behind the walls when chased.

Magically, Von Trier manages to do this even when he crafts a world with no walls. That world is Dogville, and it consists of a rectangular soundstage smack dab in the middle of a colorless, intangible ether. Dogville represents a minuscule town in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado during the Great Depression, but with its Monopoly-like etchings of houses and pathways, we understand it as being far more universal, an emblem of the blueprint by which all American (and perhaps international) small towns abide. It has a spot for the town dog that is reminiscent of silhouetted dead bodies from slapstick comedy films, a central road donned the common name "Elm St." despite the lack of elm trees, and a bench at the edge of the town designated with pedantic specificity as "the old man's bench". It doesn't matter if these things seem implausible given their assigned context (never does a certain old man even sit on "the old man's bench"); rather, they are meant to evoke a folksiness that might remind us of the small communities we have visited in our lives. Dogville is just an archaic slab of concrete onto which Von Trier has placed a group of living, breathing humans whose oblique naturalism contrasts starkly with their deliberately artificial surroundings.

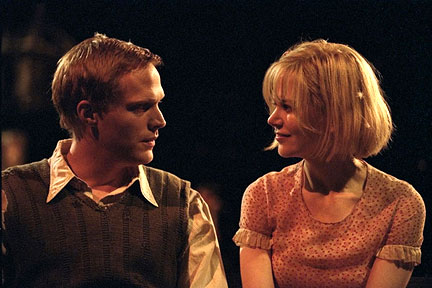

It is not long though before the initial novelty of the unique setting dissolves and becomes invisible in the face of the film's plausible drama. That is not to say that one may mistake a real door for what was really just an actor pantomiming the opening of a door to a dubbed sound effect, but there is some heightened sense of conviction that these characters are actually living a customary life on a game board. This stems from the ability of an electric cast (including Lauren Bacall, Ben Gazzara, Philip Baker Hall, Chloë Sevigny, and Stellan Skarsgård) to bring to life a believable community, fraught with their own idiosyncrasies, prejudices, and routines. For all this though, Tom Edison (Paul Bettany), the soft-spoken writer in the town, feels the community needs a moral readjustment. He sees a certain coldness in the attitudes of those around him that may be a cause of the absence of a church in Dogville.

Then, as if struck down from God, the conveniently-named Grace (Nicole Kidman) arrives in town one night to the tune of gunshots. She is a radiant blond fugitive whose seedy ties with gangsters suggests she has stumbled out of a noir film from Hollywood in the 1940's. Tom, always willing to lend a helping hand, offers to have Grace hide out in Dogville, and he sees her presence as an immediate opportunity to put the townspeople's tolerance to the test. He holds a vote on keeping her and Grace just barely survives it. Although she understands she has placed a burden on the town and is more than willing to leave without bothering anyone, she is extremely enthusiastic about assisting wherever she is needed to reverse the skepticism of those around her. Not only that, but Grace also sees Dogville as a minuscule land of opportunities, a cozy place where "hopes and dreams are pursued". Her wide-eyed eagerness in the town is similar to that of Naomi Watts' character in Mulholland Drive, albeit in a less cartoonish manner. Consequently, both actresses deliver fearless performances that require their spirits to be up one moment and down in the dirt the next, laying bare not just flesh but dignity as well.

Because of this, Dogville gradually becomes an emotionally unpredictable parable of the xenophobic tendencies inherent in a group mentality and the evil that ensues when an outsider invades the group's space, among a confluence of other issues. While Tom continues to support Grace, if not publicly then privately, the rest of the town is progressively less accommodating. Despite Grace's unerring work ethic, her schedule is pushed to extremes in order to maintain acceptance in a community that runs stolidly on the ideal of utilitarianism. Her jobs, delegated to menial tasks such as making daily conversation with the repudiating town blind-man (Gazzara) who speaks of lavish sights out his window, do little to boost her integrity as a citizen in the community. Instead, they eventually afford her rape (by an old-world farmer named Chuck, in an ascetic portrayal by Stellan Skarsgård) and a mix of glaring eyes by women who disapprove of her actions. To complicate things, Grace and Tom develop an intimate but opaque love, and by film's end, Tom is about the only male in the community who has not had the sexual privilege of Grace's body, although none of these instances are voluntary. One of Dogville's most stirring images involves the town going about its business while in the corner of the frame, through the invisible walls, Grace is being taken advantage of violently, an eloquent statement on the prevalence of violence in the most unsuspecting of places.

As well as being heavily self-referential - the film contains chapter markers that explicitly state what is about to happen - Dogville pulls abundantly from other art forms such as literature and theater and also runs through a gamut of religious allusions. Grace's predicaments align themselves well with the martyrdom experienced innocently by Christ, only here the crucifix is replaced by a heavy wheel that gets chained to Grace's body via her neck, and the people around her further echo mythological significance with some of their strategic names: Pandora, Athena, Olympia. Von Trier's penchant to mix up different reference points (Christianity and Ancient Greece) within one film is nothing new, and why exactly he does it here is open to various interpretations, but its presence undoubtedly gives the story a feel of timeless universality. More coherent is the continued use of John Hurt's ebullient narration, which offers up storybook witticisms that contrast the harshness onscreen. In this way, Dogville almost functions as a critique of the "Great American Novel", questioning the reliance on conventional storytelling as a mode of sorting out the complexities of human nature, because in the end, Hurt's narration does little to actually punctuate the intangible qualities working beneath Dogville, a film that - in all its conscious artificiality - boils down to thematic and emotional levels beneath the surface.

It is precisely this ability on Von Trier's part to convey things subtly that distinguishes Dogville from the rest of his oeuvre. So many of his films are dirtied from beginning to end by his fingerprints, and it is not often that we get that sense of unnecessary intrusion in this film. Of course, a Von Trier film is always a Von Trier film - Dogville contains handheld camerawork that is a clear descendant of his filmmaking manifesto Dogme 95 and it also boasts the director's characteristic cynicism towards humanity - but he is more often than not sitting back and letting his actors carry the film from its slow build to its shockingly apocalyptic finale, obtaining exquisite performances from Nicole Kidman and several others as a result. It's rare that I can say this so confidently about a Von Trier film, but Dogville is indeed a deeply thought-provoking, mature work of art.

No comments:

Post a Comment