Below is a complete ranking of the films I saw at the 65th Cannes Film Festival. Enjoy!

1. Holy Motors (Carax, France, In Competition)

When I saw Leos Carax's first feature in thirteen years,

Holy Motors, on the final day of rescreenings, it was by no small margin the most mysteriously beautiful, inventive film I'd seen at Cannes. Starting with the simple setup of a man working as a professional chameleon, riding a limousine stuffed to the brim with suitcases full of disguises around a serenely dreamy Paris and fulfilling different "appointments" around the city, Carax builds a multilayered meditation on performance, identity, virtual reality, and cinematic artifice. Much of the film's power comes from Denis Lavant, most deserving of the festival's "Best Actor" award, who lives each episode of the film's chronological but strangely timeless structure with the candidness and thoroughness necessary to breathe life into the film's motif of dual identities and the elusive "self". What at first seems to smell of redundancy and half-assed improvisation proves to be executed with such remarkable subtlety, grace, and precision by Carax that not a single delirious chapter - even as the director pushes Lavant to vaudevillian feats such as playing a repugnant sewer-dweller carrying an angelic Eva Mendes into his shit-stained lair, concluding with a sight-gag of Lavant's erection - feels out of place. This is a film with a fearless sense of movement and visual invention, not to mention a constant self-awareness and absurdist humor. I can't wait to see it again.

2. Journal De France (Depardon and Nougaret, France, Out of Competition/Special Screenings)

A basement full of unreleased newsreel celluloid from legendary French documentarian Raymond Depardon covering a vast range of small and large scale historical events circa the middle of the 20th century yielded the festival's most moving and poetic images. Uncovered by Depardon's wife and usual sound recordist Claudine Nougaret and positioned alongside contemporary footage of Depardon taking a photographic tour of France alone in his car, the resulting cut of

Journal De France becomes a mesmerizing essay (set to killer musical cues!) on photographic truth and how images become a mirror of one's thoughts and feelings throughout the course of one's life. Yet as much as the film is a loving portrait of Depardon the artist and man, it's also, as the title suggests, a kaleidoscopic journey through France's history, its social and cultural charms, its regrettable involvement in wars, its strange political missteps (the scene of finance minister Giscard D’Estaing describing his public marketing campaign is a particular gem), and most of all, its ordinary civilians. The film's eye, like that of its primary subject, is humble, compassionate, and patient.

3.

In Another Country (Hong, South Korea, In Competition)

The first time Hong Sang-soo's static camera compulsively snap-zoomed in on the action in

In Another Country's extended opening shot, it's as if the entire audience experienced a collective lurch towards the actors. Perhaps this impression is just to due to my unfamiliarity with Hong's aesthetic, but in any case

In Another Country provides a heightened intimacy with the filmed material, a direct relationship between director/audience and subject, and a sense of the film being conceived as it's being shot. A work so casual, spontaneous, and grounded rarely makes an appearance In Competition at Cannes, and Hong's glorious hangout of a film is all the more powerful for it. One of several films at the festival (along with

Cosmopolis,

Like Someone in Love,

Morning of Saint Anthony's Day,

In the Fog, and

Moonrise Kingdom) that seemed to exist in a deserted bubble of a world comprised only of characters in the story, Hong follows Isabelle Huppert as she materializes the incomplete scenario ideas of an aspiring screenwriter (seen in the opening shot) on vacation in a South Korean beach town. The film's effortless narrative symmetry allows one to contemplate the subtle variations in the ways Huppert's three different characters are treated by a rotating cast of locals, thus providing insights into love, life, and otherness so off-the-cuff and fluid it puts shame to more heavy-handed treatments of these motifs.

4. Post Tenebras Lux (Reygadas, Mexico, In Competition)

The obligatory pillar of provocation this year was held up by Carlos Reygadas with his new film

Post Tenebras Lux, an ambitious collage-like expression of Mexican country life that unsurprisingly garnered equal parts applause and booing. (One wonders when Cannes crowds will grow up and learn to embrace artistic license and individualistic work without resorting to knee-jerk skepticism.)

Post Tenebras Lux digresses rather significantly from the comparatively sobering and linear

Silent Light, but what it does share with Reygadas' previous work is its insistence upon making its audience feel something, and it put me in an unusually discomfiting space that I've rarely experienced from cinema. Despite some of its age-old arthouse ingredients (nature, animals, mechanical sex, an unforgivably extraneous scene of animal cruelty), the film is quite unlike anything ever made, and truly unique to Reygadas' sensibilities. A dark energy pulses through the film as the Mexican filmmaker never shies away from presenting conflicting emotions (family bliss and marital tension, tenderness and unexplained violence, religious devotion and paralyzing fear of the Devil) alongside each other with fervent unpredictability, giving its mystical and quasi-autobiographical musings a distinctly different tone than the otherwise structurally similar

Tree of Life from last year. Though Reygadas employed the suddenly in vogue but previously extinct Academy aspect ratio (the boxy, claustrophobic 4:3), no film at Cannes felt bigger or more expansive, as its loud, immersive sound design and ghostly visuals exploded from the screen.

5. Like Someone in Love (Kiarostami, Iran/Japan/France, In Competition)

I'll join the chorus of critics intrigued but somewhat baffled by Abbas Kiarostami's new Tokyo-set feature

Like Someone in Love. The film is startlingly open-ended, seeming to merely capture a few episodes in the middle of a much longer narrative, and in the thick of Cannes craziness, the mental space required to mine Kiarostami's complexity is simply non-existent. Here, the director charts a similar paradigm shift roughly at the midway point as that of

Certified Copy when the relationship between a young girl (Rin Takanashi) and an old man (Tadashi Okuno) shifts from prostitute/client to grandfather/granddaughter based on the innocuous misunderstanding of the girl's psychologically abusive boyfriend (Ryo Kase). The side-effect is an opaque investigation into the nature of social roles and perception, limited to a few interiors in Tokyo and several of the director's trademark car conversations. It's amazing how economical this film is, using such a small number of tense, protracted dialogue scenes to open up a vast ocean of mystery around these three characters, each of whom appear to be hiding something authentic and unfettered beneath their social façades.

6. Walker (Tsai, Taiwan/Japan, Critic's Week)

A new 30-minute short by Tsai Ming-Liang entitled

Walker was one of the best surprises of the festival. I'm still eagerly awaiting a new feature from the Taiwanese master, but this new work is precisely the length it needs to be. The film is decidedly, unapologetically simple, though certainly not simplistic. In it, a Buddhist monk (Tsai apostle Lee Kang-Sheng) dressed in a bright red robe walks through the hustle-bustle of Tokyo at a snail's pace to fetch a snack (this narrative detail is only revealed later in the film in an unexpected sight gag), his head perpetually facing the ground and his eyes in a meditative squint. He lifts each foot as if lifting the weight of his spirit before returning it to the ground with patience and grace. Were it not for the real-time passersby - many of whom take note of the camera's presence (adding gravitas to the performative spectacle) - one might be tempted to assume Tsai shot at a high frame-rate for slow motion. Lee's persevering slowness, his utter commitment to the act, is astonishing. Tsai shot the film himself on a digital camera with his usual frozen takes and distinctive urban framing, and the result is a remarkably pure evocation of the ghettoized pursuit of faith in the modern consumerist environment.

7. In the Fog (Loznitsa, Russia, In Competition)

An extreme seriousness towards death characterizes a great deal of the best Russian cinema, and Sergei Loznitsa's

In the Fog joins that lineage. This 2-hour opus unwaveringly explores the rocky psychological landscape of men crawling inevitably towards a not-too-distant death, meanwhile caught between the absurd pressures of patriotism and a simple respect for human existence. On the frontiers of the German occupation, Sushenya (Vladimir Svirskiy) is wrongly accused of treason by his fellow men, and escorted out of his forest home by two Russian soldiers - Burov (Vladislav Abashin) and Voitik (Sergei Kolesov) - to be killed. Happenstance has it that Nazi soldiers interrupt the scene of the punishment, and Burov becomes the wounded, setting the stage for an extended inquiry into the ethical dilemmas of war under a misguided regime. Loznitsa's dialogue-heavy script - set entirely within the confines of the grey and foreboding woods - often stumbles and crawls, and, in its lack of variety, clearly shows the effects of working with limited funds (this is a film that could have benefited greatly from a more palpable sense of surrounding context), but

In the Fog is nonetheless the most stirringly spiritual feature of the festival.

8. Morning of Saint Anthony’s Day (Rodrigues, Portugal, Critic's Week)

There's not a single horizon line visible in João Pedro Rodrigues' 30-minute short

Morning of Saint Anthony's Day, and it creates a powerfully destabilizing effect. Paired in a Critic's Week program with

Walker, the films share a quiet observation of people walking through an urban space, but here there is an enigmatic undertone - teased out directly late in the film when one girl's

Twilight Zone-esque ringtone sounds - of science-fiction and campy genre cinema that allows the images of a swarm of young adults emerging to level ground from within subway stations to suggest a kind of post-apocalyptic zombie invasion. Rodrigues covers all of the action - teenagers throwing up, keeling over inexplicably, walking into city ponds while holding up their cellphones seemingly in search of service, etc. - from vaguely aerial perspectives, bolstering the uncanny effect of the happenings. Is this a metaphor for the somnambulistic state of contemporary techno-youth, or is it just an unconventional vision of the undead traversing a posthuman landscape? The film's only press blurb is of little help: "Tradition says that on June 13th, Saint Anthony’s Day – Lisbon’s patron - lovers must offer small vases of basil with paper carnations and flags with popular quatrains as a token of their love."

Morning of Saint Anthony's Day is an inspired oddity.

9. Amour (Haneke, France/Germany/Austria, In Competition)

Michael Haneke's

Amour is an unapologetically traditional, by-the-numbers European arthouse film centering on the big themes of mortality, love, grief, family, and humiliation. Which is not to say it's fraudulent or insincere, just that it's precisely the unflinching film one would expect Haneke to make on the topic of an aging couple slowly coming to terms with death. Every formal strategy (detached wide shots, measured cutting, muted colors), narrative jolt (sudden violence, a metaphorical bird entering a French apartment), and casting decision (Jean-Louis Trintignant, Emmanuelle Riva, and Isabelle Huppert as the central family) is justified and expected, but as a Bergmanesque chamber drama it lacks the magic and complex humane treatment of Bergman. In

Amour, death divides a family, and Haneke, amazingly precise as he is, can't put forth an image of postmortal hope that is very convincing, instead preferring to unceasingly pick apart the physical and psychological strain of aging and death. There's an abysmal fear in this film that's disguised as cruel realism.

10. Lawless (Hillcoat, USA, In Competition)

John Hillcoat's

Lawless, previously known as

The Wettest County in the World and based off the book of the same name, received some undue critical hounding after its premiere, which is strange given that it's a pretty bareknuckled and well-made Western, nothing more and nothing less. Sure, Hillcoat waters down any moral ambiguity that might have existed in the film's awkwardly schmaltzy epilogue, and the sexual landscape leans towards vaguely misogynistic, but I'll take some of these missteps over

The Road's simple-minded affectations of importance and superficially "contemplative" mise-en-scène. What's more,

Lawless is chock full of thrilling performances by Tom Hardy as a daftly philosophizing brute, Gary Oldman as an indifferent mobster, Guy Pearce as the slimy villain, and Shia LaBoeuf (!) in his best role as a wannabe tough guy. Still, the greatest source of my enthusiasm for the film was the immaculately dusty and contrasty cinematography of Benoît Delhomme, who shoots these Prohibition-Era ghost towns - always wafting with the smoke of whisky and brandy production - in an undeniably conventional yet painterly manner. It's a ruthlessly brutal genre movie that for quite some time maintains an air of Peckinpah-like stoicism.

11. Lawrence Anyways (Dolan, France, Un Certain Regard)

Another year of inclusion in Un Certain Regard for Canadian filmmaker Xavier Dolan represents yet another example of the mainstream hesitance to embrace youthfulness in auteur cinema. Surely,

Lawrence Anyways has more personality, and is more expressive and heartfelt, than a number of the Competition entries, and it could have added further diversity to the lineup, especially in light of its focus on social minorities (specifically a transsexual intending to remain in a heterosexual relationship). Dolan's films clearly emerge from a passionate and genuine place, and their energy and messiness is entirely the product of a spontaneous excitement for cinema. Needless to say,

Lawrence Anyways is sloppy, overlong, and digressive, but the strange allure of Dolan's work is that he manages to absorb these flaws into the texture of his character's lives, discovering ways to transform self-indulgent slow-motion shots (this one has even more than

Heartbeats) into gaudy expressions of a character's veiled insecurity or overblown self-importance. Like Dolan's main character,

Lawrence Anyways is split between two urges: that of individuality and personal fetishism (the film's often radical compositional style and its Felliniesque eccentricities, to name two), and that of conformity (its fiery scenes of romantic turmoil featuring a revelatory Suzanne Clément and its eye-rollingly sappy denouement, both of which achieve Hollywood rom-com stature). Upon close inspection of the film's insanity, it's not too difficult to see the structural design on display.

12. The Hunt (Vinterberg, Denmark, In Competition)

Thomas Vinterberg's a director with a clear interest in the secrets lurking beneath the complacent surfaces of Danish communities and families, and he's exercised that concern yet again in

The Hunt, a finely wrought but quickly forgettable drama about a Kindergarten teacher (Mads Mikkelsen) who is angrily cast off from his circle of friends and colleagues following the random lie of his female student (Annika Wedderkopp). There's a palpable socioeconomic and cultural infrastructure in the film's small town, as well as a solid sense of verisimilitude that must come from Vinterberg's years as a Dogme ascetic, but at the same time there's a sluggishness, a beating-around-the-bush quality to the film's narrative progression, as if Vinterberg has merely set up a troubling scenario to relish in his formidable knack for depicting societal disintegration. Furthermore,

The Hunt feels too much like just a good story that was put to film, rather than a story that was expanded upon and expressed vitally through cinematic means. It's a small distinction, but it's the one that prevents Vinterberg from being as distinctive a director as he could be.

13. Moonrise Kingdom (Anderson, USA, In Competition/Opening Night)

The Darjeeling Limited suggested a director trying to engage with issues broader than his own tiny universe and

Fantastic Mr. Fox showcased an artist's desire to work with a new approach, but

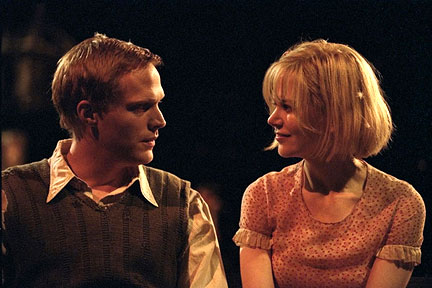

Moonrise Kingdom represents a firm step back into the confines of Wes Anderson's own headspace, and at this point the refusal to make artistic evolutions more drastic than the simple changing of a typeface and the move away from anamorphic widescreen is somewhat damning. The film feels decidedly small and inconsequential, failing to achieve the surprise emotional punch or sprawling canvas of films like

The Royal Tenenbaums and

The Life Aquatic. Furthermore, Anderson puts the burden of the film's momentum in the hands of two unknown child actors (Jared Gilman and Kara Hayward) who just cannot carry a scene or portray pre-pubescent love in a convincing manner. As usual for Anderson,

Moonrise Kingdom is aesthetically irreproachable, shot with an oppressively diorama-like sensitivity and production designed to fantastical perfection, but it puts its eggs in the wrong basket narratively, all while wasting the naturally Andersonian flair of Anderson newcomers Bruce Willis, Edward Norton, Frances McDormand, and Tilda Swinton. My love for Anderson aside, and despite a hilariously overblown climax that utilizes some throwback color toning,

Moonrise Kingdom is a frustratingly flimsy act of regression from this important American filmmaker.

14. Cosmopolis (Cronenberg, USA, In Competition)

The humid theater it screened in was of no help to David Cronenberg's already-stuffy

Cosmopolis, the experience of which was akin to being suffocated by the director as he whispered his esoteric contemporary philosophies in your ear. Well, more precisely, Robert Pattinson, who has become the inert mouthpiece for Cronenberg's meandering and impenetrable dialogues on the current state of economics and politics. It's clear enough that this is the story of the 1%, but I'll admit total confusion and ignorance towards the remainder of Cronenberg's intentions, and I'm certainly not prepared or interested in trying to shuffle through the needlessly coded meanings in this never-ending string of talk. Intellectual detachment is all well and good though if Cronenberg were at least able to present his ideas in compelling cinematic fashion (hence the success of

Like Someone in Love) rather than resorting to what feels like characters reading manuscripts to each other in a black box theater. The outside world is so closed-off and pared-down in

Cosmopolis that it's as if any of Cronenberg's decisions apart from the dialogue (the NYC location, Pattinson's plot-churning desire for a crosstown haircut, the rat as a symbol of the deteriorating dollar) were arrived at arbitrarily. Add to this the flat digital cinematography and

Cosmopolis is just a dull, unimaginative slog of a film.

15. The Paperboy (Daniels, USA, In Competition)

Ok, at least Lee Daniels dropped the wacked-out racial hierarchy of the abominable

Precious, but in its wake he's yielded a frankly incompetent, meaningless, and misguided tribute to the low-budget homespun camp cinema of the film's 1960's era, and he's traded the revolting view of inner-city blacks in the previous film for stereotypes of southern white trash in this one. Surely,

The Paperboy aims for ickiness, but to what end? In a climactic sex scene between recently-released criminal Hillary Van Wetter (John Cusack) and blonde bombshell Charlotte Bless (Nicole Kidman), Daniels cuts to images of livestock as a punctuation mark, as if deriding his characters' baseless behavior. As much as the film tries to approach a sympathetic note for its depraved characters in the end, for the most part it rides this reprehensive wave throughout, and it presents it all in a psychosexual storm of bad editing and crummy lighting. Zac Efron stumbles away with some surprisingly nuanced acting as a detective's (Matthew McConaughey) younger brother and a man struggling with overwhelming physical desire for an Kidman's older character, but otherwise the cast appears confused, seemingly lost in Daniels' inexact mise-en-scène, unaware of whether or not the cameras are rolling. This is a profoundly awful film.