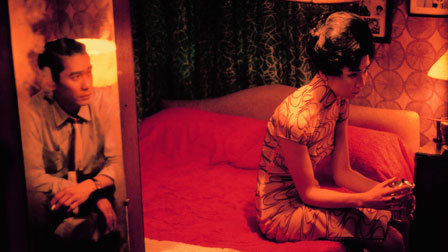

Over at In Review Online, Kenji Fujishima has rallied together a "Directrospective" on the films of Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar-Wai. The series has been covering, chronologically, one Wong feature per day since August 13th, all leading up to the American release of his long-awaited martial arts epic The Grandmaster. Today, I weighed in on 2046, Wong's brilliant oddball of a "sequel" to In the Mood for Love (2000). It's my first perfect four star review for the site, which gives you a quick sense of how deeply this film affects me. Be sure to check out the other astute entries in the series as well!

Over at In Review Online, Kenji Fujishima has rallied together a "Directrospective" on the films of Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar-Wai. The series has been covering, chronologically, one Wong feature per day since August 13th, all leading up to the American release of his long-awaited martial arts epic The Grandmaster. Today, I weighed in on 2046, Wong's brilliant oddball of a "sequel" to In the Mood for Love (2000). It's my first perfect four star review for the site, which gives you a quick sense of how deeply this film affects me. Be sure to check out the other astute entries in the series as well!

Showing posts with label Chinese Cinema. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Chinese Cinema. Show all posts

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

2046 (2004) A Film by Wong Kar-Wai

Over at In Review Online, Kenji Fujishima has rallied together a "Directrospective" on the films of Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar-Wai. The series has been covering, chronologically, one Wong feature per day since August 13th, all leading up to the American release of his long-awaited martial arts epic The Grandmaster. Today, I weighed in on 2046, Wong's brilliant oddball of a "sequel" to In the Mood for Love (2000). It's my first perfect four star review for the site, which gives you a quick sense of how deeply this film affects me. Be sure to check out the other astute entries in the series as well!

Over at In Review Online, Kenji Fujishima has rallied together a "Directrospective" on the films of Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar-Wai. The series has been covering, chronologically, one Wong feature per day since August 13th, all leading up to the American release of his long-awaited martial arts epic The Grandmaster. Today, I weighed in on 2046, Wong's brilliant oddball of a "sequel" to In the Mood for Love (2000). It's my first perfect four star review for the site, which gives you a quick sense of how deeply this film affects me. Be sure to check out the other astute entries in the series as well!

Monday, October 17, 2011

Gatekeepers: Tarantino v. Besson?

A concept such as a “Gatekeeper Auteur,” as outlined by Leon Hunt in his book East Asian Cinema: Exploring Transnational Connections on Film, is less a useful critical term than a vague and pedantic categorization. Hunt uses the term to refer to Quentin Tarantino and Luc Besson, two Western director/producers – one American, the other French - who are “attuned to cults surrounding Hong Kong, Japanese, and South Korean cinema” and end up “displaying their connoisseurship of Asian cinema” in their films. Tarantino is the more flagrant and unapologetic of the two, as well as the figure that is seemingly less at fault, while Besson reveals his fanboy status through allegedly invisible appropriations. For instance, the agile street fighting and urban parkour of Besson’s Banlieue 13 shares a kinship to Chinese martial arts, while Tarantino’s much-lauded Kill Bill series has an aesthetic field day with the Shaw Brothers, Yakuza films, Seijun Suzuki, Bruce Lee, and Takashi Miike, among countless others.

The more one digs into the surfaces of Kill Bill and Banlieue 13, however, the less they really seem to represent any sort of binary representation of Asian cinema influence. To what extent are Tarantino and Pierre Morel (Besson’s hired director) really operating on different ethical planes? How is Morel’s borrowing of a twice-recycled tagline recipe (“No Wires, No Special Effects, No Limits”) not a blatant admission of homage in the way of Tarantino? How is it fair for Tarantino to overflow his film with snatches of canonical influences whose specificities are likely to fly over the head of the majority of the target demographic and unfair for Morel/Besson to take the lesson of no more than one Asian reference point (the Kung-Fu street fighting of Ong-Bak) and let it billow to the surface only sporadically throughout the course of an entire film? (That David Belle’s pectorals remain elegantly exposed for much of the running time isn’t enough to concede Bruce Lee theft). Both directors seem to take sly advantage of their viewers - merely a fraction of which probably have any clue what’s being plundered – to present images and forms that fly as “homage” to one crowd and as “originality” to another.

Either way, there’s a long lineage of artistic borrowing that the directors are continuing here, a trait that hearkens way back to the earliest practitioners of motion pictures and even beyond the cinematic medium itself. Hunt problematically seems to draw the line of acceptability at this notion itself rather than at the particular modes of borrowing the filmmakers indulge in, as if to suggest that most American narrative cinema since the 1930’s is somehow “Russianized” because of its indebtedness to Eisenstinian montage, or that Godard is a phony because of his regurgitation, and simultaneous commentary on, a hodgepodge of global cinemas. Artistic recycling may be erroneous in the case of Morel/Besson and Tarantino, but it is so for different reasons, none of which include the mere fact that they are resorting to Eastern media consumption as influence.

It is a crucial distinction here that Tarantino is unabashedly honest and borderline arrogant in his film-literacy while Morel/Besson are more populist and unassuming in their ambitions. Nearly every shot and every sequence in Kill Bill is spiritually tethered to a similar moment in a marginalized (by Western standards) Asian Kung-Fu film, yet Tarantino’s ultimate resignation to “Orientalist tropes of impenetrable psyches and exotic otherness” betrays his appreciation. This is one area where Hunt nails it, discussing how Tarantino can only "have Asian" and not "be Asian." Morel and Besson feel no inclination to loudly proclaim their idolatry, instead disguising their influences in the comparatively unique French habit of parkour, which is questionable in an altogether different way. They, on the other hand, "have Asian" without seeming to desire to "be Asian", preferring to morph to their own context. The “right” thing to do here – that is, the approach that yields the greatest degree of respect and admiration and the lowest levels of hasty exploitation – is perhaps somewhere in the middle.

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

Happy Together (1997) A Film by Wong Kar-Wai

Although Happy Together is only one of two of Wong Kar-Wai’s films to be set almost exclusively in the Western Hemisphere, it perhaps more pointedly concerns the Hong Kong Condition than any of his Hong Kong-set films. The year of its release is of fundamental significance; 1997 was the year that Hong Kong would forgo its position under the colonial rule of Britain and return its sovereignty to mainland China. Curiously enough, as a colony of Britain since it was ceded in 1841, Hong Kong is a space associated more with Britain than with China, and it possesses a destabilized historical and political identity that could only be further confused by its belated assimilation into Chinese culture. As such, issues of identity and stability abound in Wong’s film, and its plot of two young gay lovers relocating for a vacation in Argentina right in the midst of this national event is a fittingly exaggerated concession of spatial displacement. Buenos Aires, conveniently, is a port city much like Hong Kong, a place of heedless immigration and expatriate activity - indeed, the mirror image of Hong Kong as implied by Wong's upside-down shot of the city late in the film. From this contextual foundation, Wong builds a film about the search for connection and meaning in an environment that seems incapable of offering such rewards with people who seem blind to them.

Happy Together’s abstracted representation of Argentina - all time lapse, claustrophobic interiors, and heightened colors - becomes a surrogate for 1997 Hong Kong, where transients have been assigned a newfound sense of identification, just as Ho Po-wing (Leslie Cheung) and Lai Yiu-fai (Tony Leung) assert themselves into the Argentinean milieu that is simultaneously strangely familiar and foreign. The lovers go to the city in the first place to visit the Iguazu Falls, a vast waterfall canyon that comes to represent an unattainable oasis as their relationship gets increasingly unstable, breaking out in fits of rage and jealousy that keep them confined to a tiny, dilapidated apartment room within the city. Wong bookends the film with a magnificent aerial shot of Iguazu, its dark mist billowing from the gulf in between. It's very likely the same image used twice, but it nonetheless transforms from something that is sublime and seductive to something forbidding and impersonal, a powerful indication of how turbulent Ho Po-wing and Lai Yiu-fai's journey is and how much intimacy Wong is able to capture in the process. Like their own native city, the location has become warped and unreal, no longer possessing its initial magic and seemingly inhospitable to life.

The lovers' relationship is plagued from the beginning of the film by bitterness and jealousy, and only fleetingly interrupted by rare moments of compassion and physical contact. Wong’s extratextual context suggests that the trauma of the lovers is due largely to a missing basis of stability. Both men’s families are out of the picture, underlining Hong Kong’s larger issue of social division and individualization, and one gets the sense that Ho Po-wing and Lai Yui-fai would completely disappear were it not for their frail connection to each other. They're both true wanderers, lonely souls without a clear idea of what they are searching for or what they want out of each other. While Lai Yui-fai internalizes his disappointments, Ho Po-wing returns almost nightly bragging about his sexual encounters and ordering treatment for his cuts, bruises, and broken bones, symptoms of a dangerous and unfaithful lifestyle. In many of the film's finest scenes, Leung and Cheung deftly convey the schizophrenic tendencies of a relationship without defined boundaries, swapping mid conversation to become the powerful or the powerless. Wong's sympathy generally leans towards Lai Yui-fai, the more sensitive of the two, but he invests compassionately in the rebellious, traitorous Ho Po-wing too, who finds himself alone in their Argentinean apartment without Lai Yui-fai late in the film, one of the many instances in Wong's filmography of characters connecting through absence. So often it is distance - not proximity - that denotes intimacy.

This sentiment is stretched to a subplot involving Lai Yui-fai's co-worker at a tourist-friendly Chinese restaurant in Buenos Aires named Chang (Chen Chang), a character who is only introduced late in the film at a time when Ho Po-wing is at his most emotionally distant. Lai Yui-fai, despite his intentions of indifference and overwhelming feelings of heartbreak, relays an instant, if hesitant, connection to Chang. Their time together is limited to the fast-paced kitchen environment where they work and where Chang regularly stays overtime to survive financially, but when Lai Yui-fai cooks him dumplings one night it immediately recalls his similar nurturing of Ho Po-wing in his time of injury. It's a relationship that never moves beyond the platonic (there are the minor details, too, that prove Chang is straight), yet there is an undeniable charge in their shared moments, especially considering Chang is hyper-sensitive to Lai Yui-fai's emotional state given his unusual condition of heightened hearing and defective sight. As is so typical of Wong's films however, potential connections are swiftly extinguished as people are separated geographically, succumbing to the flow of the impersonal globalized environment. Still, in a poetic epilogue intercut with Ho Po-wing's embrace of a Iguazu-themed lamp that sits in the lovers' apartment throughout the film, feelings of attachment are memorialized across spaces, as Chang listens to a tearful voice recording of Lai Yui-fai in a remote region in the south of Argentina and Lai Yui-fai visits Chang's family business at his home in Taipei. Material evidence of connection trumps connection itself.

These memorials also point to a potent longing for a paradise, for something beyond the ordinary (family, new locations, love), which can be linked to Hong Kong prior to British colonization. Such a backwards-looking perspective necessarily shrouds the future in uncertainty, leading to Ho Po-Wing and Lai Yui-fai’s failure to commit. It’s as if in setting his film in a foreign land, Wong is suggesting that 1997 marks the complete and utter disappearance of Hong Kong as an independent culture and the reinvention of the city as something alien even to longtime inhabitants. The lovers feel a desire to leave because they feel the growing disconnect from permanence and tradition. Not only is Hong Kong displacing itself from the country that afforded it the luxuries of capitalism for over a century, it is also attaching itself to a country that is now comparatively less developed in the avenues of technology and economy. Therefore, a radical illusion of a temporal shift occurs: the future, represented by Hong Kong’s vast technological gridlock, is returning to the authority of a politically distinct and technologically slower China, emblematic of the past. All of this leads to a heightened fracturing of time, which has forever been Wong’s visual forte. Happy Together, despite adhering to a linear narrative approach, utilizes an editing system that implies a disruption of chronological time, jumping occasionally from the urban squalor of Argentina to the waterfall at Iguazu, or taking jarring stylistic leaps such as from black-and-white to color, or from film noir to romance. The outside world is reduced to a blur, whipping by these characters in their walled-off torments, either right-side-up or upside-down.

Ho Po-Wing and Lai Yui-fai’s romance becomes an allegory for the turbulence of this uniquely global city, comprising as it does an initial level of comfort, then a prolonged era of confusion and frustration, and finally a complete extinguishing of affect, a disappearance of the entity. But Wong does not view this new phase with total cynicism; rather, his perspective is surprisingly light and forward-thinking, shedding the melancholy weight of the narrative proper at the end to muse on the possibility of new connections. (The inevitable subject of the film’s title perhaps has more to do with Lai Yui-fai and Chang’s tenuous relationship than with the unstable romance at the center of the plot.) While Hong Kong threatens to reduce the characters to ghosts without identities wandering in a limbo state between constancy and progress, they have continued to deal with these conditions by leaving, splitting apart, regrouping, and starting anew; always restless, Wong's lonely figures are at the very least striving for something meaningful.

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Cyclo (Xich lo) A Film by Tran Anh Hung (1995)

The traditional tenets of a Westernized concept of a nation – those of family, gender difference, and cultural identity – have been splintered beyond recognition in Tran Anh Hung’s Cyclo. In the overcrowded post-war ghetto of Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, characters sleepwalk through their daily grinds, taking whatever meager job they can get to struggle by. It's a place of perpetual hustle-and-bustle, an assault of urban stimuli that Tran captures in a collage of fleeting impressions ranging from labor to violence to sexuality to spirituality. The film’s central focus is an impressionable teenage boy who is identified in the script - like the rest of the figures who are defined by their professional type - only as Cyclo, the name given to the tricycle taxi he peddles around to carry supplies from one place to the next. When he is beaten up and his mode of transportation is stolen by a group of thugs, Cyclo’s already thin grounding of stability and identity is forced into flux as he descends into a shady underworld of violence, drugs, and sex.

It’s a scenario that is instantly familiar for its allusions to Vittorio De Sica’s neorealist classic The Bicycle Thieves as well as countless gangster films exploring the subject of innocence lost, but Cyclo’s brilliance lies less in its recycled narrative than in its harrowing depiction of a bruised nation, something it effortlessly aligns with the fate of its protagonist. Tran’s presentation of Vietnam overtly dissects the archaic metaphor of the “national family” by shattering every potential local family in the film. Since his single sibling (Tran Nu Yên-Khê) and mother lead lives just as turbulent as his, Cyclo is conspicuously lacking in any routinized domestic experience, and a gaping absence of a father figure is carved into the film’s DNA. The immaterial presence of Cyclo's father is felt only through periodic bits of poetic narration, seemingly the only fragments of wisdom handed down to Cyclo before his likely death in the war. It is telling that the only fathers in the film - Cyclo's grandfather (Le Kinh Huy) and the father (Din Tho Nguyen) of the gangster leader known as "The Poet" (Tony Leung) - are impotent and irrelevant to the progression of the narrative, wiling away in their drab apartment buildings smoking cigarettes. Without a firm sense of immediate family to fall back on, generations of young people are absent of moral guidance and thus, Hung suggests, turn to illegal activity to scrape by.

While Tran's representation of this illegal activity as reducible to the trades of drugs, sex, and violence may be a deterministic oversimplification of the vast scope of post-war Vietnamese societal degradation, it's important to note that he's attempting to work through the tactile grit of the everyday to get to the level of the allegorical. Characters are unnamed because they are microcosms of more widespread trends of hardship. Cyclo's sister, who is whored out by The Poet, is not necessarily an instrument of Tran's misogyny but rather a symbol of the lamentable tension that forces women in this society to resort to their bodies to get by. Interestingly enough, some of the real movers-and-shakers of this fatherless milieu happen to be women, as glimpsed in the shadowy old mob boss who mediates the economy-defining world of drug and sex trafficking. Alternately, The Poet, her leading subordinate, questions his position of authority in leading his overanxious thugs through a carnival of violence that escalates further and further away from perceivable motivation and logic. (Leung is quietly devastating in the role, even as his actions can be whittled down to moodily smoking cigarettes and dispassionately stabbing victims.) Such imbalances between youth and old age, action and inaction, knowledge and leadership, not necessarily themselves indicative of disorder or chaos, at least point towards a radical reordering of social and national identity as well as a profound disillusionment with morality.

Cyclo meticulously ties its central concepts back to potent visual metaphors nestled within. Tran presents a country forever scarred by violent American occupation during a vicious and prolonged war with an onslaught of intense, savage imagery. His critique of the needless exploitation of the Vietnamese public is never less than teeming with anger, as he frequently collides moments of relative serenity (schoolchildren singing, Cyclo joking with friends, his sister enjoying a night of glamor) with harsh jabs of inner-city bombast as if to juxtapose What Could Have Been with What Is. Accordingly, his camera leaps from being controlled to agitated, with nearly kaleidoscopic bursts of ugly color and movement. Violence sprouts within the film like a tree, branching out to its several characters until Cyclo himself is so entrenched in memories of it that he too loses a sense of rationality; he douses his body in bright blue paint in the climactic scene of the film to signal a complete retreat from reason (and to clarify that Hung was absorbing Pierrot Le Fou at the time). The collective burden is often anthropomorphized, too, in both the shot of a lizard's tail being cut off, in a poultry slaughterhouse (a savagely beautiful scene), and in the throughline involving a fish tank in the mob apartment. There's an inherent imperialism reflected in the gangsters' ownership of the fish that is not unlike that of the American relationship to Vietnam during the war, and when Cyclo stuffs his dirty head into the fish tank in one scene it's a similarly disruptive force.

The integration of violence into the flow of everyday life seems an irreversible phenomenon for the nation of Vietnam, where demoralized endeavors of violence are spread to new generations with regularity. A potent indicator of this fluid assimilation is the omnipresence of liquids - mud, water, paint, blood - in many of the film's compositions. Everything feels soaked in grime, and it seems inevitable (though Tran leaves it up in the air as to whether there is optimism or pessimism to be taken from his recurring shots of schoolchildren) that this dirt will trickle into the incoming generations of Vietnamese people. Tran’s vision of the battered nation is perhaps best visualized by the sight, late in the film, of a goldfish floundering on a wooden floor. Like the fish, the nation, seized and left to die by an outside force, is struggling to survive.

Friday, February 12, 2010

In the Mood for Love (Fa yeung nin wa) A Film by Wong-Kar Wai (2000)

Mr. Chow (Tony Leung) and Mrs. Chan's (Maggie Cheung) coincidental romance is doomed from the start. The two have moved into neighboring apartment rooms in Hong Kong on the same day, and just as soon as this happens they suspect both of their respective traveling spouses of infidelity. In the instance of mutual dejection, they begin seeing each other rather routinely enacting rehearsals of the imagined romantic liaisons of their spouses, a sly narrative device that only superficially masks the pair's own growing attachment. Yet we know from the outset that this is a relationship that will not work, if only for reasons outside their control, and director Wong Kar-Wai laments this fact while emphasizing it through tight domestic compositions and a rich patchwork of fragmentary scenes in which words are schematic and desires are withheld. The acute sense of melancholy and longing that imbues In the Mood for Love is masterfully realized through Wong's impressionistic sensibility, and it results in film that, despite its deliberately elusive narrative, which constitutes a memory of the past rather than a present moment, acquires a plausible emotional register. Everything that is mere stylistic flash in Wong's earlier films works marvelously here, as it's always stressing the underlying emotions and themes in the film, and also - being a film that is consciously constructed of moments as opposed to chronological sequences - the precise feelings inherent in every memory.

The immediate discontinuity between In the Mood for Love and Wong's earlier Hong Kong-set films like Chungking Express and Fallen Angels is the level of design precision. His early films display a burst of Godardian energy, seemingly subject to great spontaneity and fluctuation between script and finished product. Here, no notes are bent. The art direction, costumes, cinematography, and musical cues feel so pre-ordained and exact despite the film's strangely episodic, elliptical nature. Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung's meta performances are assured and mannered yet not without a sense of humor and imperfection, unlike the freewheeling naturalism of Fallen Angels' sprawling, hyper-kinetic bodies in urban spaces. Although the bulk of Wong's core collaborators remain the same (William Chang is the film's editor, and Christopher Doyle once again lends his talent to the film as cinematographer), In the Mood for Love calls upon Wong to adapt. Its story emphasizes ephemerality as well as formality (the setting is of established middle-class adults in a pivotal early 1960's instead of disillusioned twentysomething loners in a more modernized urban environment), so the style works accordingly. Scenes are alarmingly short and to the point but still beautiful, and that is very much the ulterior motive: the lovers' milieu is only deflating and suppressing the impassioned attraction at the core of their encounters.

Yet the pacing of the film also bends to the mechanics of memory on occasion. Because of the fact that Wong ends the film on Mr. Chow during a lush coda in the midst of Cambodian ruins, and positions its final quotes as those of Mr. Chow, In the Mood for Love presumably is the product of his memory. Therefore, moments of glimpsed tenderness between Chow and Chan are normally protracted by Wong through either slow-motion, matched harmoniously with Michael Galasso's mischief-soaked waltz, or nearly imperceptible shutter speed effects which retain real-time diegetic audio (such instances are infinitely more effective than their overuse in Fallen Angels). Mr. Chow savors these fleeting hints at fully expressed love with Mrs. Chan, and through the magic of his mind, and the cinematic medium, he can extend them, fetishize them, and even repeat them, explaining the several repeated scenes (and images) in the film. We are however left without the subjectivity of Mrs. Chan, and her ambivalent, emotionally confused presence in the film leaves her actual thoughts up to interpretation, but through minor, evocative gestures, Wong (and Cheung) suggests that Chan's repressed feelings are reciprocated.

In the Mood for Love is a decidedly personal, introspective work, but it also has a compressed social and political component to it. In a perfect world, free of societal constructs and points of view towards marriage, loyalty, and manners, Mr. Chan and Mrs. Chow would go unrestricted with their desires, falling for each other the moment their first instinctual love bug crawled out. Repressed romances in the face of a collective society is a storytelling plug as old as dirt, identifiable in the literary works of Shakespeare and subsequently throughout film history, most radically practiced by Luis Buñuel. Wong's film breathes interesting new life into this theme because the rapturous, rainy Hong Kong that Mr. Chan and Mrs. Chow occupy is far from being an oppressive area. Rather, the gorgeous wallpaper and meticulously placed old-fashioned cars are reflective of an adequate, even luxurious Hong Kong, and the economic situation of the time is what initially brings the pair together in the adjacent apartments in the city. As the 1960's progressed, the social situations worsened, culminating in a series of subversive riots in 1966 and 1967, when the film spends its final where-they-are-now episodes. The coming-together of Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan occurs at a highly specific time and place, and the precise conditions of their meeting could not be replayed, demonstrating the impact of the public on the personal.

Given the film's adeptness in conveying the intangible through clever visual and editing rhymes, it becomes rather redundant when Wong adds the captions referring to Mr. Chan in the final acts, phrases which add verbal verification to the broader feelings communicated through the film. This has the unfortunate effect of showing and telling, of limiting the potential for cinematic reflection to what is spoken in summation. "The past is something he could see, but not touch. And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct." In the Mood for Love does not need these words because it has an uncanny ability to make us live this experience of transience and forgetting, to truly feel the sensation of a blurred snapshot. Every ecstatic detail - the bottom of a red window shade blowing next to the floor, a cigarette in an ashtray smacked with fresh lipstick, the rotting texture of a cement wall beside the noodle house - accumulates to convey this with expertise. It's a film whose richness confirms Wong Kar-Wai as a major talent.

Friday, July 17, 2009

Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky (Lik Wong) A Film by Ngai Kai Lam (1991)

Today in mainstream, lowbrow action films, movement and viscera comes and goes at a fast pace, and blood and guts often follow in synchronicity. When a character reaches for his gun in a dark alley, he is bound to shoot. When a simmering femme fatale puts a knife to the throat of a fraudulent punk, she will most likely either slash his neck open or at least give it in a pinprick as a warning. But what often exists in these encounters is a dangerous sense that the actors don't have any dedication to their malign roles. Moreover, the construction of such scenes involve all the rigor and creativity of a chore. The directors behind the work have a predetermined idea of where they want to take their action aesthetically and narratively, so when fight scene after fight scene slips by on the screen, it seems as if they are merely getting on with it, creating the scenes for productivity's sake.

Such insistence upon proficiency and reliance upon tried-and-true technique is wholeheartedly absent from the Hong-Kong manga-inspired flick, Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky, a popcorn movie that is so gleeful in its bad taste and its joyous maximalism that it becomes viscerally draining in its own way. The film involves something about an excessively hostile prison, an imprisoned flutist named Ricky with superhuman strength, a "gang of four", which are the four outrageously subhuman masters of each prison sect, a romance between Ricky and his girlfriend, the vengeance of whom got him into jail in the first place, and oppressive authorities. Any attempt that the film makes at a statement on the abusive, corruptive nature of authority however, is ultimately undermined by the sheer absurdity on display. The story is so inconsequential, the characters so shred-thin, the scenarios so unbelievable, that any encapsulation of the plot remains entirely unnecessary. I still cannot, for the life of me, decide why a fat, greedy little boy shows up at the prison in the end with his domineering father to egg on all matters of violence and obsessive torture, and, echoing some ludicrous back-story that occurs offscreen, frighten the larger, more threatening inmates with his mere presence.

What makes Riki-Oh such a hoot to watch is the gung-ho attitude on the part of the filmmaker, Ngai Kai Lam, that permits him to obey this credo: "if it's shown fast enough, maybe people will believe it." Of course, this is never the case, and as a result we can identify the clearly discernible tin foil - meant to stand in for an iron door - that Ricky jumps through, the ridiculously doctored facial grotesqueries when someone's skin is slashed off, or the obtuse physical movements during fight scenes that don't, by any stretch of the imagination, seem practical. Every time Ricky punches an opponent, he tears clean through their bodies. In an act of desperation, one of his adversaries unravels his own large intestines to strangle Ricky. When all is said and done though, Ricky's outlandish physical strength is too much for his opponents. But simultaneously, via sporadic inner monologues and flashbacks that come so infrequently that they cease to be devices at all, we see that Ricky is really a gentle human being, resolute in his fight for justice. This is all narrative hogwash, but Ngai truly believes in it, and what he brings to the assembly line of blood and guts is not determined professionalism, but rather enthusiastic amateurism that delights in every second of fantastic cinematic realization.

Saturday, December 13, 2008

Still Life (Sanxia Haoren) A Film by Jia Zhang-Ke (2008)

In many ways, Jia Zhang-Ke's 2008 feature Still Life is modern China's answer to Antonioni's L'Avventura. The backdrop is a flooded Fengjie, whose weathered remnants of buildings are being demolished by workers for low pay, a project deemed the Three Gorges Dam (Yung Chang's recent documentary Up the Yangtze covered the same topic). Jia creates an interesting snapshot; workers are being rewarded to destroy the city of their past lives - thus contributing to China's rapid industrialization - to allow for a new neighborhood to be built. Like L'Avventura, the environment is one that is jostled and undergoing inevitable modernization.

Jia introduces a coalminer from Shanxi who is in search of his past wife and eventually his daughter. His pursuit begins with motivation, but is diverted by the demands of the scrambled climate and the rich social fabric that Jia presents. About one quarter through the film, a nurse, also from Shanxi, arrives with her own set of goals: finding her more immediate husband. Amidst these catastrophic times, there is a noticeable decline in human values and an unfortunate inability to establish an identity and mold past relationships. Antonioni's film dealt with similar thematic ground: the failure of personal identity and by extension, the advent of isolation in a changing world. When the coalminer and nurse do finally meet, there are no fireworks. Each of them realize what has been lost and cannot be salvaged; the result is an uncomfortable vow for remarriage between the coalminer and his ex-wife, and a sad agreement to divorce between the nurse and her husband.

Jia typically refrains from deep characterization however to revel in the awesomely beautiful setting with HD video. In fact, scenes involving an influx of characters are often shot in deep focus to dissolve the protagonists into the anonymity of their surroundings, making them just one in the crowd. Such interiors, which often involve a crowded grouping of people in anguish, are shot quite spaciously, allowing for the viewer to almost feel the breeze coming through the broken walls. One calmer shot fantastically composes five shiny bare-chested workers seated closely eating bowls of noodles. Still Life succeeds the most however when the camera quietly observes the deconstructed landscape with a splendid use of natural light. Immense pan shots reveal ravishing juxtapositions of foreboding mountains adorned by fog, decrepit buildings inhabited by ghostlike silhouettes of men hammering away at the bedrock, and a glistening Yangtze river. Jia's perceptive attention to detail is exhibited in these fine pieces of photography and in the rhythmic sound design of the workers' clanking.

Unfortunately, the dazzling fiction/documentary fusion is interrupted occasionally by the surreal: a UFO speeding by the vista or a building's infrastructure lifting off like a space shuttle. Jia discusses how the setting seemed to him like it had fallen prey to an alien attack, but if these images are some puzzling result of mass dementia, I feel they are not aptly suited (not to mention they are distractingly digitized). This minor flaw unfortunately feels like vital punctuation and not simply visual flair. Without a doubt though, Still Life, like L'Avventura, displays with eloquence the personal effects of a wavering environment.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)